American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger is credited with popularizing the term “burnout” in the 1970s to describe the impact of severe stress on workers in the “helping professions” (Freudenberger, 1974). He noticed that dedicated doctors and nurses volunteering at a busy, free, New York City clinic would often end up exhausted and unable to cope.

Since this initial research, burnout has been observed among stressed-out workers in many other industries and professions such as teachers, military personnel, police officers, managers, elite athletes, social workers, human service professionals, lawyers and people working in the financial sector (Heinemann & Heinemann, 2017; Poghosyan et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2020).

Professor Christina Maslach was one of the pioneers of burnout research in the late 1970s and early 1980s and is still one of the most prominent scholars in the field. She, along with her colleague Susan Jackson, identified three dimensions of burnout (Figure 1):

- exhaustion,

- cynicism, and

- inefficacy, a lack of accomplishment and reduced productivity (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

Figure 1. The three dimensions of burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

Maslach and Jackson’s research led to the development of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), the first questionnaire to scientifically measure burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). This tool, now in its fourth edition (Maslach et al., 2018), is still widely used by researchers today (Heinemann & Heinemann, 2017).

The World Health Organization (WHO) publishes the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). It may surprise you to learn that “Burn-out” appeared for the first time in the latest edition, the ICD-11 (2019). This is because WHO does not consider burnout to be a medical condition. Rather, they define it as an occupational phenomenon and a factor influencing health status (World Health Organization, 2019).

The signs and symptoms of burnout

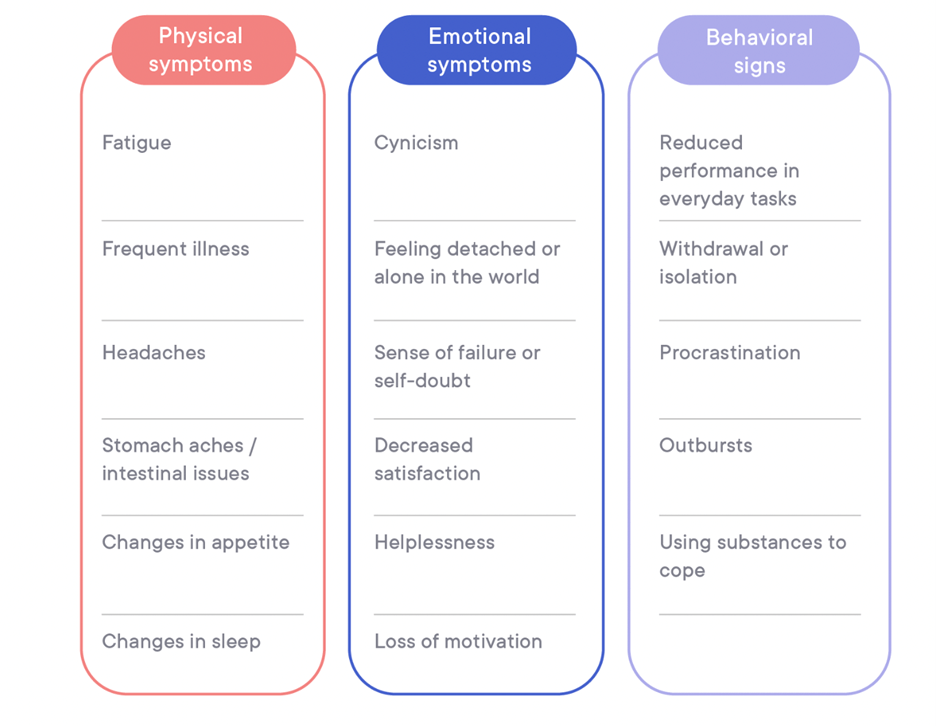

Maslach & Jackson’s definition provides a ‘high level’ picture of burnout but may leave you wondering exactly what this phenomenon looks like in practice. Darling Downs Health, a division of Queensland Health, organizes the signs and symptoms of burnout into physical symptoms, emotional symptoms and behavioral signs (Table 1).

Table 1. Signs and symptoms of burnout (Darling Downs Health, 2021).

The personal toll of burnout – effects on the body and brain

Burnout involves chronic activation of the body’s stress response system, otherwise known as fight-or-flight. This can lead to diseases such as diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease (American Psychological Association, 2018). As you are probably aware, prolonged stress also has a negative effect on the immune system which makes us susceptible to infections. This is why one of the physical symptoms listed in Table 1 is ‘frequent illness’.

The impact of burnout is not restricted to the body. Research involving brain scans shows that “the emotional turmoil of burnout leaves a signature mark” on the brain (Michel, 2016). People formally diagnosed with burnout show differences in the amygdala, an area involved in emotional reactions, and the medial prefrontal cortex, which is involved in executive functions such as working memory, flexible thinking and self-control.

The point here is that although burnout is not recognized as a medical condition, it does involve profound changes to the body and brain. It impacts our thoughts, feelings and behaviors and should not be ignored.

Practical Exercise: Identifying burnout

The Mayo Clinic (2021) has compiled a list of questions to help identify burnout based on the common signs and symptoms.

- Have you become cynical or critical at work?

- Do you drag yourself to work and have trouble getting started?

- Have you become irritable or impatient with co-workers, customers or clients?

- Do you lack the energy to be consistently productive?

- Do you find it hard to concentrate?

- Do you lack satisfaction from your achievements?

- Do you feel disillusioned about your job?

- Are you using food, drugs or alcohol to feel better or to simply not feel?

- Have your sleep habits changed?

- Are you troubled by unexplained headaches, stomach or bowel problems, or other physical complaints?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, you might be experiencing job burnout. However, you could also have a medical condition such as depression, anxiety or chronic fatigue syndrome. The Mayo Clinic recommends talking to a doctor or a mental health provider for an accurate assessment. If your workplace has an Employee Assistance Program (EAP), consider making an appointment. If you are a leader or manager, it’s especially important to attend to your own mental health as well as that of your team.

Key Takeaways

- Burnout involves feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, increased mental distance from or cynicism related to one’s job, and reduced professional efficacy.

- According to the World Health Organization, burnout is a work-related syndrome.

- Burnout involves physical and emotional signs and behavioral symptoms. Burnout affects both the body and the brain.

- If you feel burned out, pay a visit to your doctor or mental health professional. Burnout should not be ignored.

Related Reading

- Why Mental Health is Not the Opposite of Mental Illness

- Resilience: What It Is, What It Is Not, and Why It Matters

- How Nutrition Impacts Your Mental Health

References:

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Stress effects on the body. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body

- Darling Downs Health. (2021). Signs you might be experiencing a burnout and how to regain balance in your life. Queensland Government. Retrieved from https://www.darlingdowns.health.qld.gov.au/about-us/our-stories/feature-articles/signs-you-might-be-experiencing-a-burnout-and-how-to-regain-balance-in-your-life

- Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff Burn-Out. Journal of Social Issues, 30(1), 159-165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

- Heinemann, L. V., & Heinemann, T. (2017). Burnout Research: Emergence and Scientific Investigation of a Contested Diagnosis. SAGE Open, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017697154

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99-113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (2018). Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Manual 4th Edition: Printed for shipping. Retrieved from https://www.mindgarden.com/maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi/686-mbi-manual-print.html

- Mayo Clinic. (2021). Job burnout: How to spot it and take action. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/burnout/art-20046642

- Michel, A. (2016). Burnout and the brain. Association for Psychological Science. Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/burnout-and-the-brain

- Poghosyan, L., Aiken, L. H., & Sloane, D. M. (2009). Factor structure of the Maslach burnout inventory: an analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. International journal of nursing studies, 46(7), 894-902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.004

- Wang, J., Wang, W., Laureys, S., & Di, H. (2020). Burnout syndrome in healthcare professionals who care for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 841. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05694-5

- World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases